Red Link [Citation Needed]

A new wiki for the risograph community!

Interrupting the two other substack posts in the queue (they've been there a while) to bring you: a quick write-up on helping George Wietor launch the new stencil.wiki!

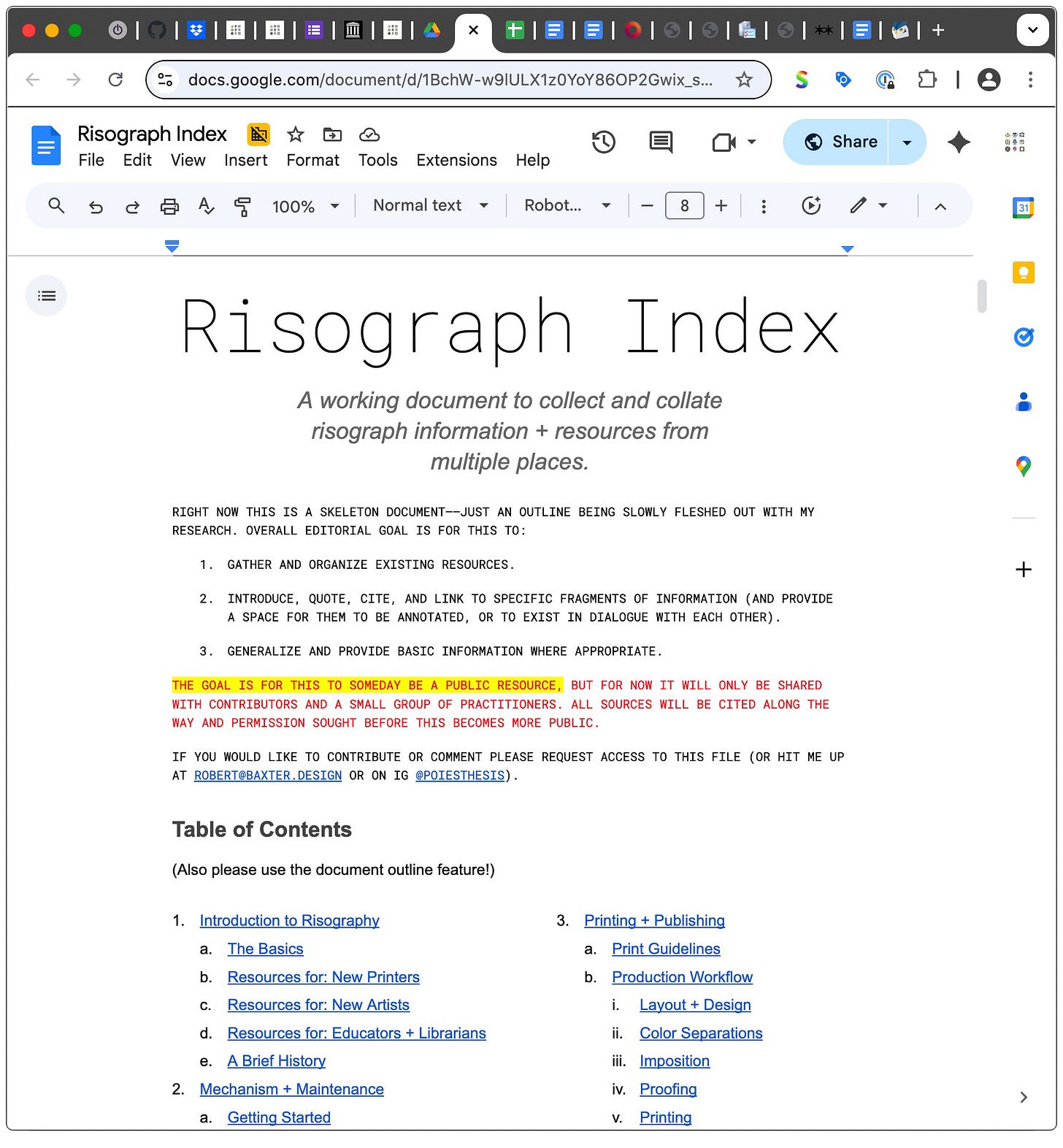

We've redone the wiki—it was an undertaking! The bulk of this article is sort of how that came about, and why, and the odd writing experience it's been for me to work on. I'm sharing this because: (1) I think wikis are great (one of the vestiges of those earlier promises of the internet and one of the few places online that a democratization of information is actually practiced); and (2) I went into this fully blind, so I wanted to document a bit of what I learned along the way.

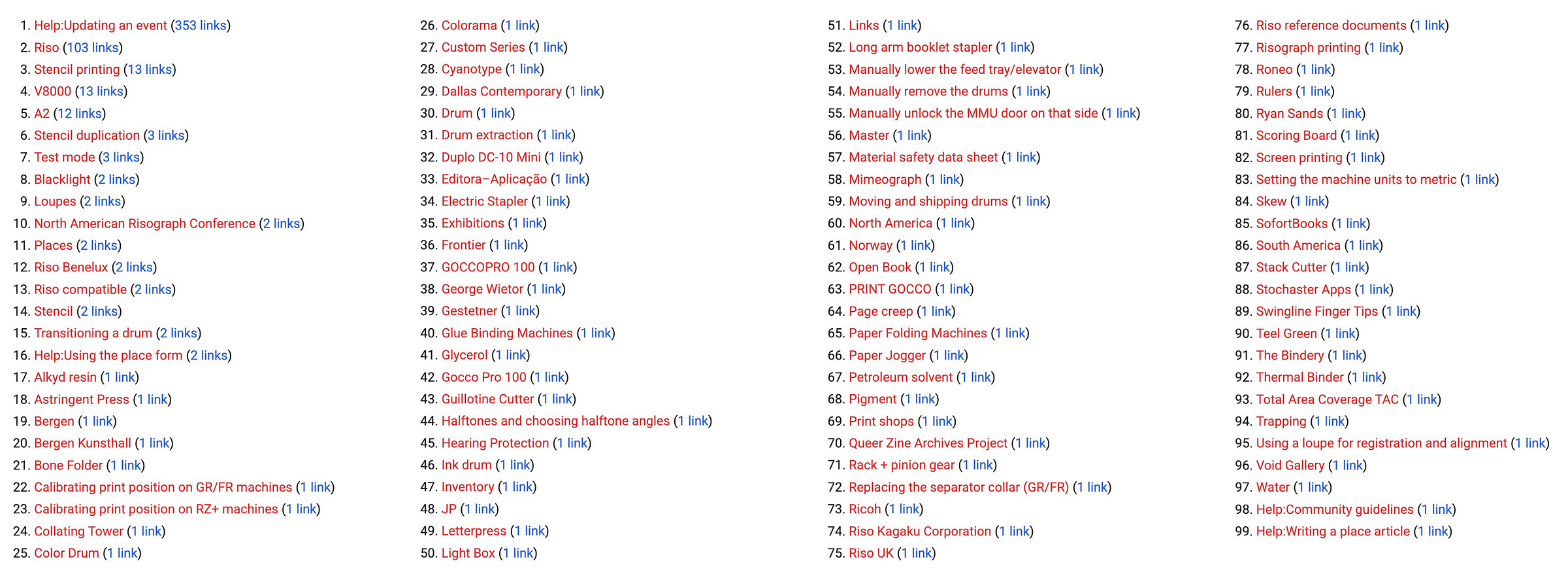

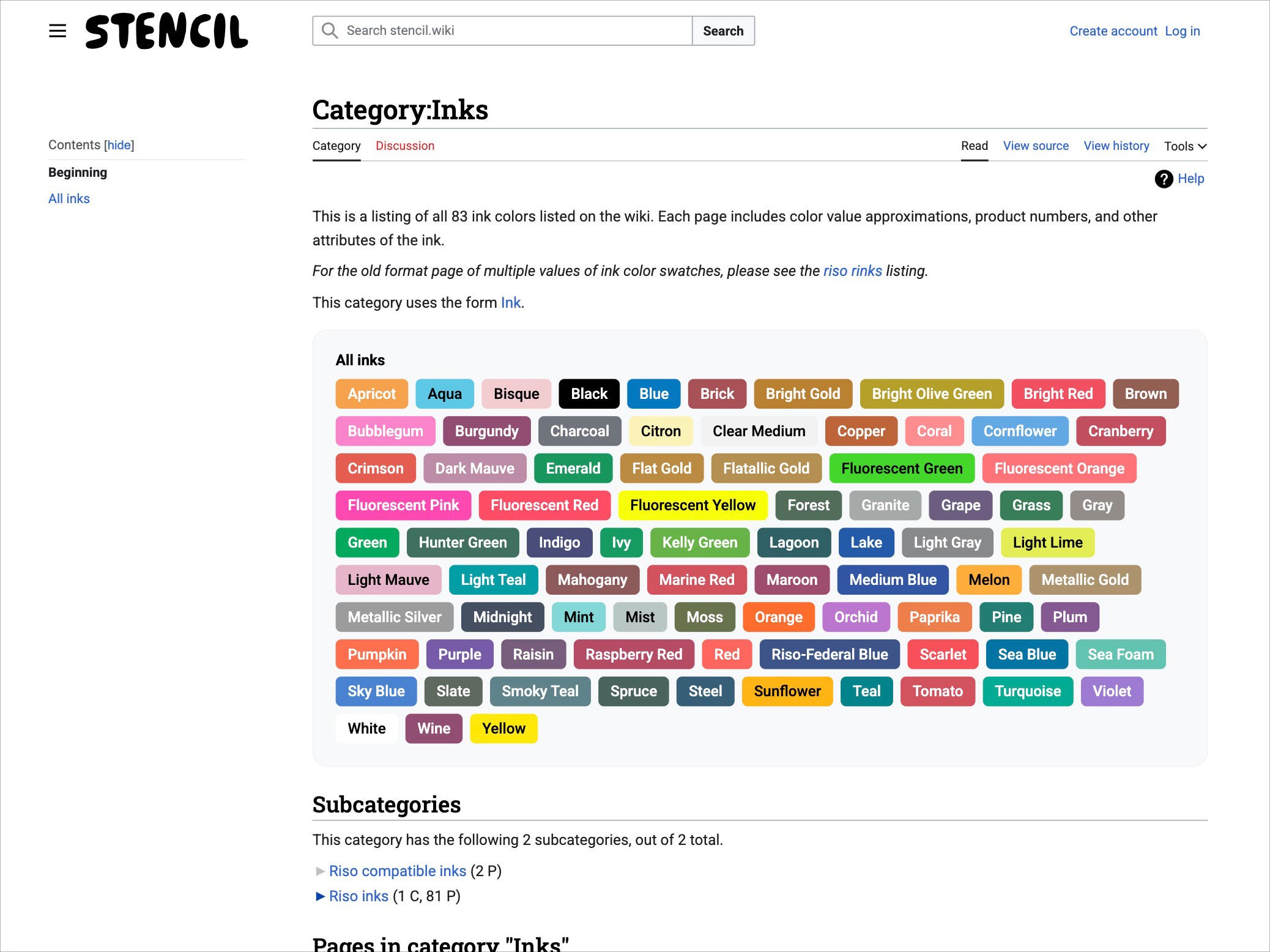

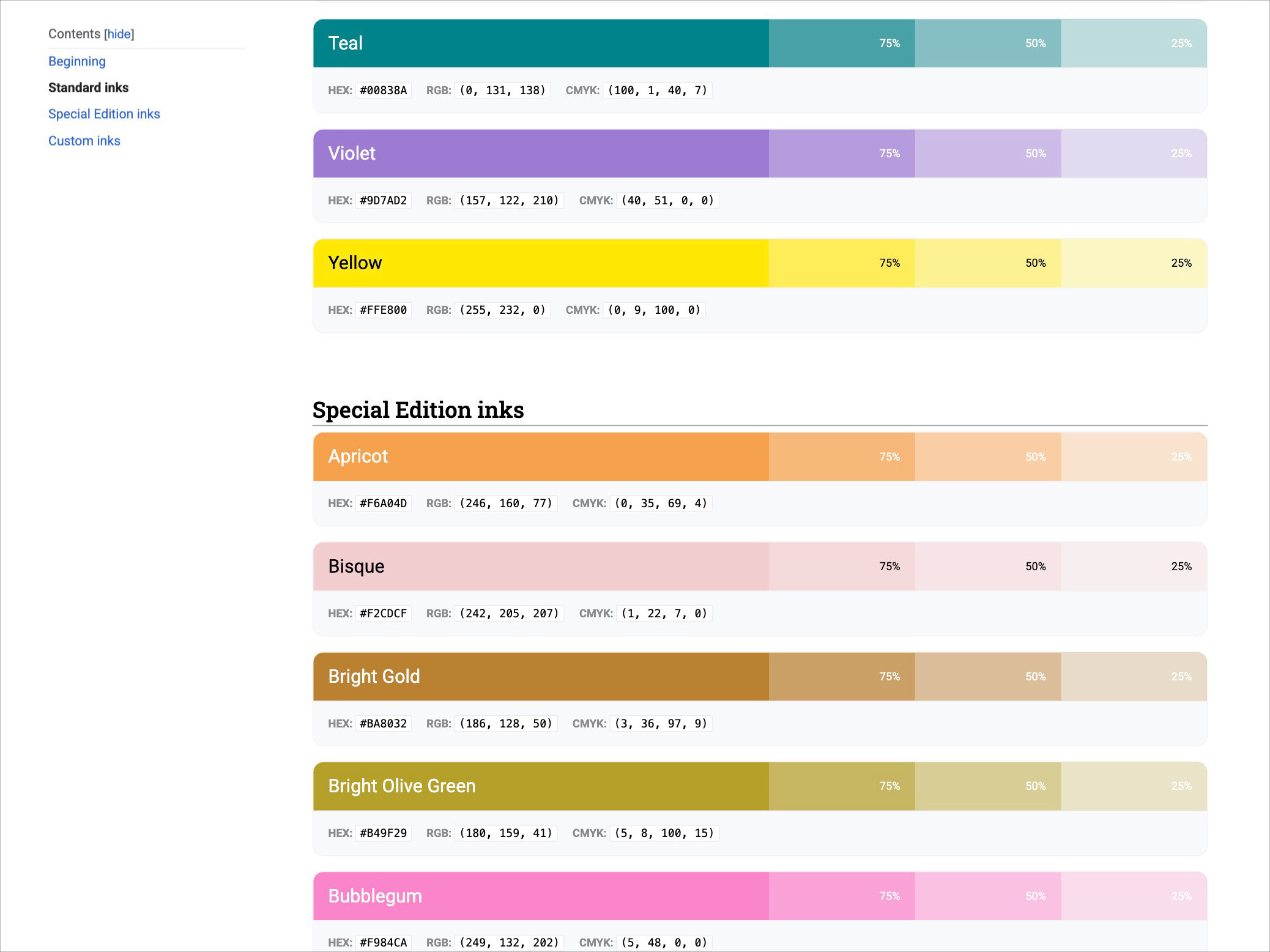

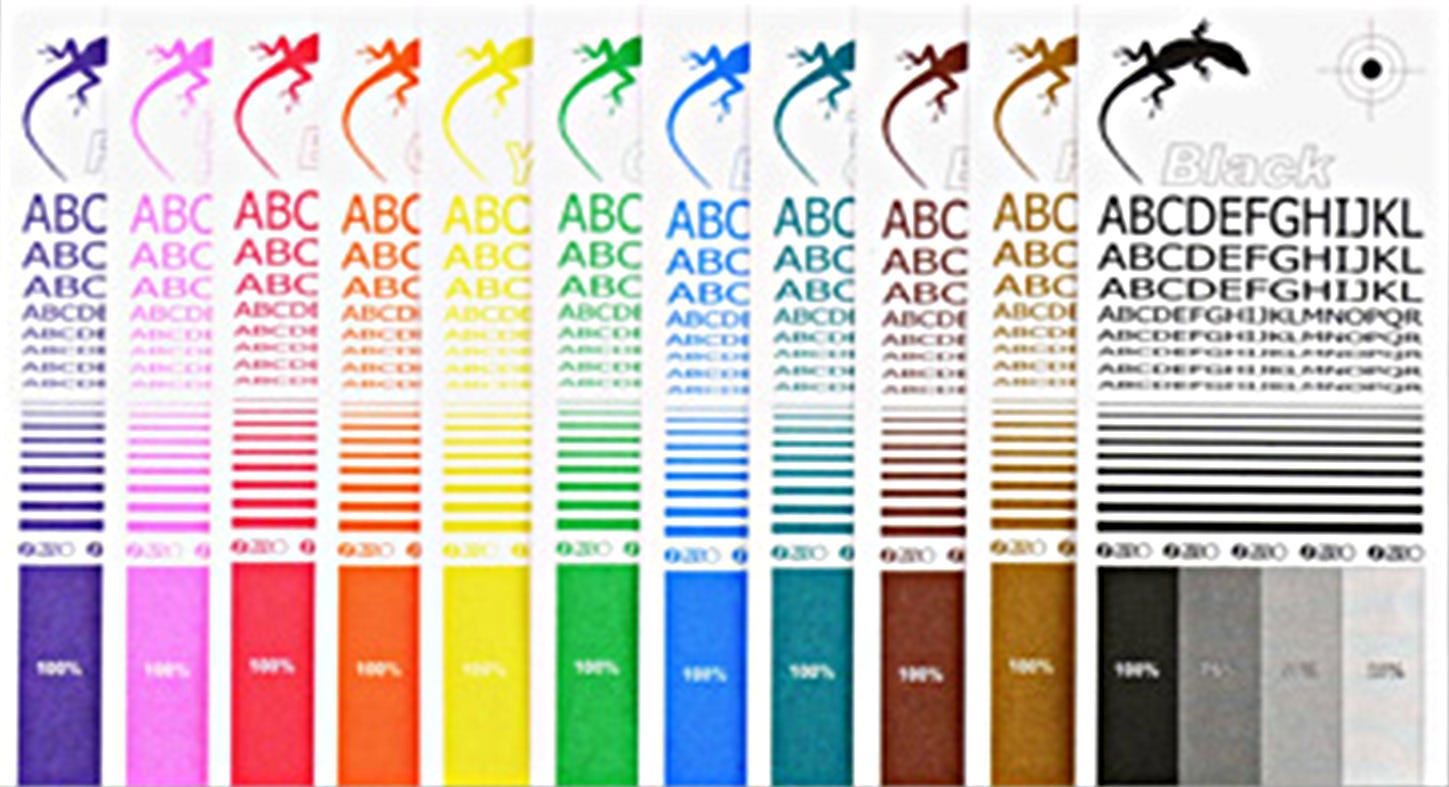

But first the fun stuff—what we've made! Here's some excerpts:

And this is all now live and in the public air—anyone (or you) can browse and contribute to it!

An Atlas of Modern Risography

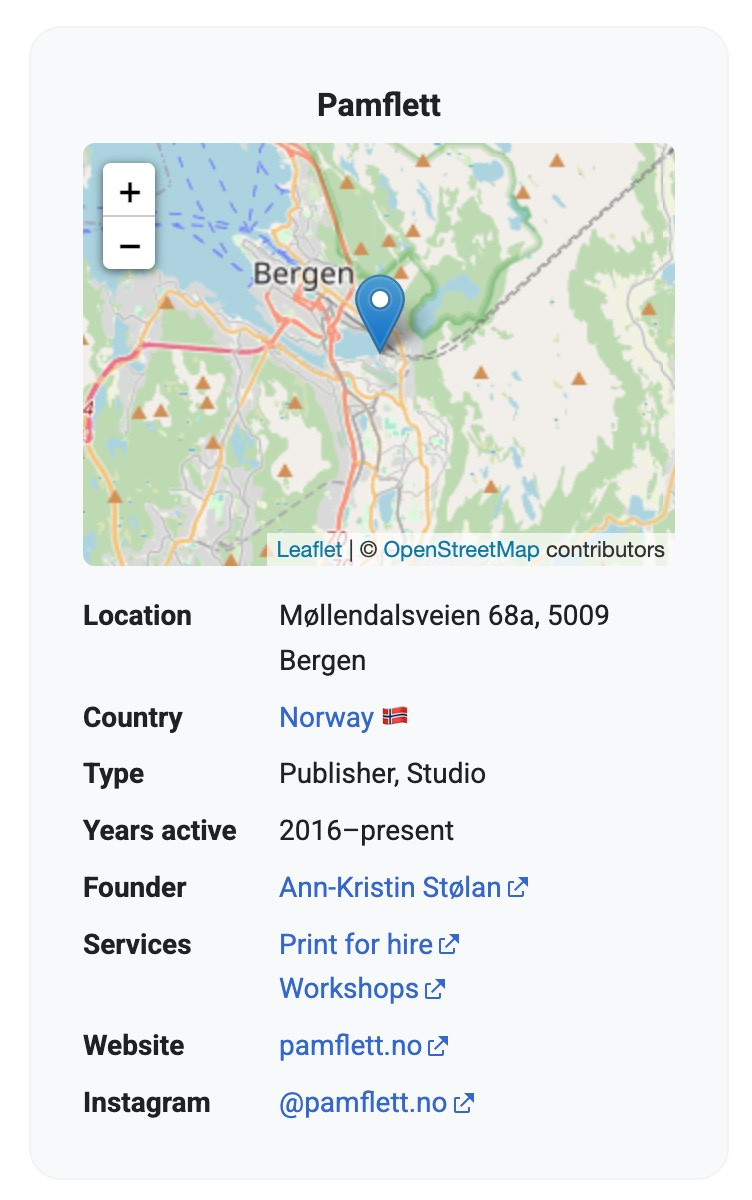

For those not in the know, stencil.wiki is a community-edited site for all things risograph. It got its start about 12 years ago, when George Wietor (who I think a lot of us consider one of the pillars of this community) wanted to map out everyone who was doing this form of printing. We're all quite dependent on each other in this little world (take that as broadly as you like), and figuring out who is where and doing what is pretty useful information to have and share! It's also the kind of directory that is sort of foundational to fostering a dispersed dialogue amongst presses. Maybe not the only part of the foundation, but some necessary wrought iron work. It gave something for the rest of us to fill into and take form with.

This was the original "Atlas of Modern Risography," it debuted in 2014 at the first Magical Riso conference at the Jan Van Eyck Academie in Maastricht, Netherlands. Generally one would use it to look up:

Riso presses in your area, or a place you were visiting.

People using the same machines as you (this is where I started when fixing my first riso—and found Small Works, The Center for Imaginative Cartography & Research, and Sometimes Publishing as a result—all other FR3950 users at one time or another).

People who were running a certain rare color of ink—like White or Metallic Gold or Fluorescent Yellow that you wanted to use on a project.

Spaces that offered print for hire, residencies, or other such fare.

Then, as it expanded to include more riso-related things, you'd also use it to find:

Which zine and book fairs were on the horizon (and had open applications).

Some specs on the machines themselves (and occasionally a PDF of a technical manual or sales brochure)—including exactly how many years ago your beloved printing friend was discontinued ☹ (23 years for mine).

A handful of community contributed articles about maintenance or hacks or other resources.

And it did a great job! Especially considering that when George originally built it, he made it more or less from scratch (which is a huge undertaking—in his day job, George is a website person)—but as it scaled up it got clunkier and clunkier. And for as much useful info was to be found—it was non-intuitive to add to or edit—so it was hard for the community who relied on it to contribute to it. As a result many of us built our own little independent resource lists, spread out around the internet.

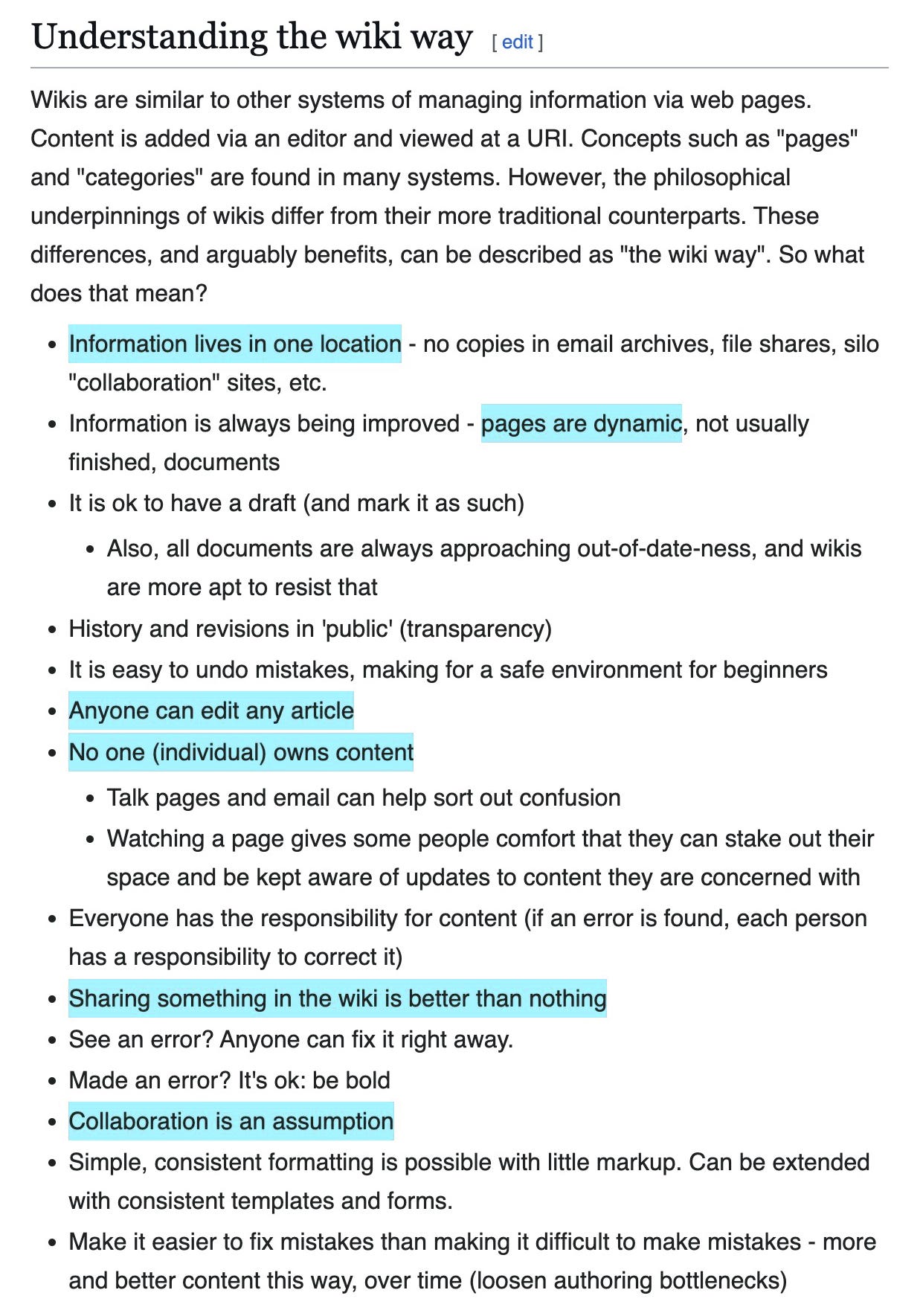

What is a Wiki?

When we think of a wiki we generally think of wikipedia.org (remember when it used to be considered a bad source compared to what else you could find on the internet? we were so young)—as it's more or less the originator and the most prominent example. But the pattern has been generalized, now there's lots of wikis! (I mostly run into them in my own world as fan built documentation for indie games and old TV shows.)

Generalizing a structure like "wiki" as a type-of-thing, that anyone can use or implement, means you need/want two basic systems:

A philosophy or ethos of use (what is it used for and by whom, how should you be able to use it, what should it have in it, how should it be written, what should it feel like—what exemplifies it from other-types-of-things?)

A means of implementation (some type of way to actually make the thing exist).

Here's an excerpt of some of that wiki philosophy:

One of the issues we were running into with the old wiki is that while it supported a lot of those values, it was falling short of some of the key ones—namely the editability and shared ownership—and was sort of stagnating as a result. The overall structure of ehat sorts of things were there or could be there, was pretty set in stone, and changes to it would require a lot of work from George to code up. And while the articles held a lot of useful information, they were all written from the perspective of a single contributor (whoever wrote it initially), so they were quite static—not a collective voice that others could edit, update, or improve on. This method of individual ownership also led to a lot of redundancy, and old, outdated information.

A lot of this came down to the fact that it was all built from the ground up, and had to make up its own rules along the way! Which is how we end up building a lot of things as a community. But, it had sort of grown as far as it could in its current shell

To address all this, George and I, in conversation with Amelia Greenhall (of Anemone, Kathleen Sleboda (of Draw Down), Ben Grzenia (of bearbear) and a few others online—decided to take the plunge and change the second of those systems—the implementation.

While you can implement the philosophy above on a custom thing, there a few major platforms made especially for wikis (think of a platform like a big robust toolset, a tangible thing—unlike the ephemeral philosophy above)1—and we ended up going with MediaWiki. You're probably familiar with it! It's what Wikipedia runs on—that's part of why we went with it, the familiarity. Everyone knows how to navigate it! And more and more, people know how to contribute to it too—plus there's loads of documentation, support and packages (additional functionality that people have added, like maps).

Here's more or less what it had built in:

Anyone can set up an account to start adding or editing pages. And all work on the wiki is tracked and can be reverted/recovered, annotated, etc.

A template system for building out modular elements that can be repeated throughout the wiki (more on this below).

A simple mechanic for managing internal and external links to the wiki (including the red links after which this post is titled—more on those below too).

A categorization structure to allow pages to be grouped and found as groups.

Search functionality.

Support for a lot of customization and styling/appearance.

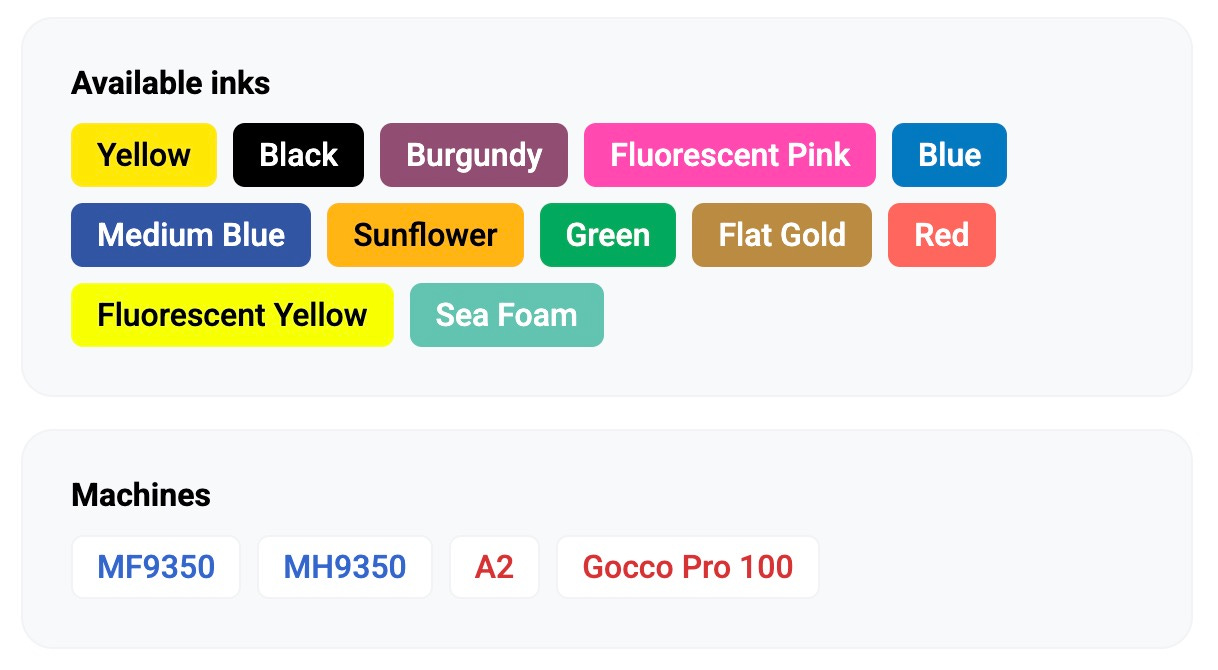

A means of scripting some more complex behaviors + math stuff (like how we determine whether the text on those little ink swatches in those excerpts above should have white or black text).

A whole bunch of management tools, like page metadata (we can know what pages haven't been edited recently and flag those as maybe needing a once over, for example), mass editing, user permissions, backup and security stuff, etc.

Our job was to recreate all of the functionality of the last site (and all the information it held, including 1000+ studios and 700+ events) and to expand it to be more editable and have the capacity for much of the future plans we were incubating! The in-the-box stuff got us most of the way there, but we also added some packages in order to support:

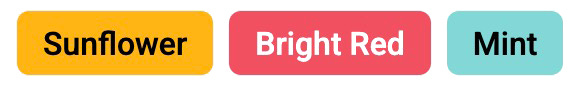

Data storage and retrieval (implemented with Semantic MediaWiki)—this is a big one, as it allows us to reference the information written on one page in a different page. Mostly wikis are strung together with links between pages, but the stuff on the page itself just lives on that page. With data stuff though, we can just have the hex value for Sunflower (#FFB511) defined somewhere on the Sunflower page and then on any other page where we want to show that color, we can just ask the Sunflower page what its hex code is!

Simpler editing tools for pages, including with forms (web classic, we love/hate a form) (implemented with Page Forms), and a WYSIWYG editor (implemented with Visual Editor)—so that people don't have to use any code to make complex pages.

A map display (implemented with Maps) so that we could recreate the atlas!

Figuring out all of these packages was quite difficult, we tried out a bunch of different options to see how things played together or didn’t and if they could support the vision for how we wanted the wiki to work and where it might go. So many test pages on different setups, reading often limited documentation, and lots of looking through examples of each package in use on other wikis—before we finally found a combination that (mostly) worked for our needs.

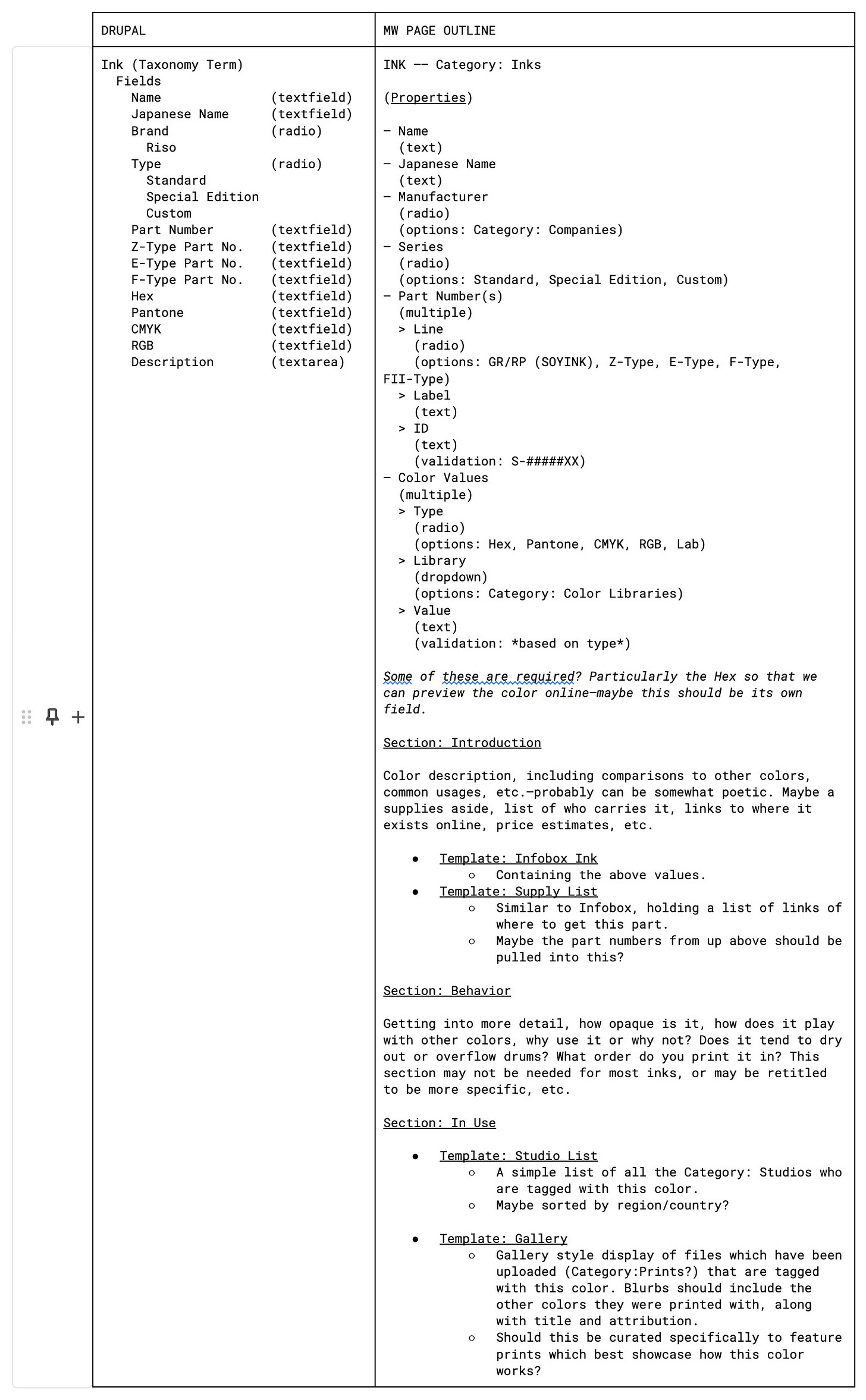

Architecture of Objects

The next principal task was to essentially define all the patterns of what kinds of things would exist on the wiki. At least the first definitions of them—part of the plan is that both the definitions and the sorts of things we are defining can grow and change. I refer to this as the architecture—the plans of the sorts of things we can build.

A quick aside on architecture architecture—it's not a thing I do, but I run across it, and its methods all the time. Two architect friends of mine, Jackie Hensy and Tristan Walker explained to me (during an exhibition we were working on together) that the way architectural plans work is that they are not a full detailing of absolutely everything in a building—not like a LEGO manual. Rather they are a system of rules which govern how the bits and pieces go together in all their potential scenarios and configurations. So you aren't specifying where every outlet is, or every tile—you are explaining how outlets are positioned relative to the walls and corners and doors and the like, or how the tiles go around corners or meet with moldings. Then those rules are applied to the skeleton of the building and the result is the actual structure. And that part of the game of architecture is to make those plans as simple as possible, and elegant in their simplicity.

What does this mean? Well first we have to determine the "objects" of the site, the types of things—pages that should share a common structure. Then for each object, we have to figure out everything we need to know about it, all the informational stuff.

On the wiki so far, our types are: Places (printshops, publishers, bookstores, venues, etc.), Events (mostly fairs, but also conferences and workshops and stuff), Inks, Duplicator series (i.e. GR, RZ, SF, MH, etc.), and Tutorials.

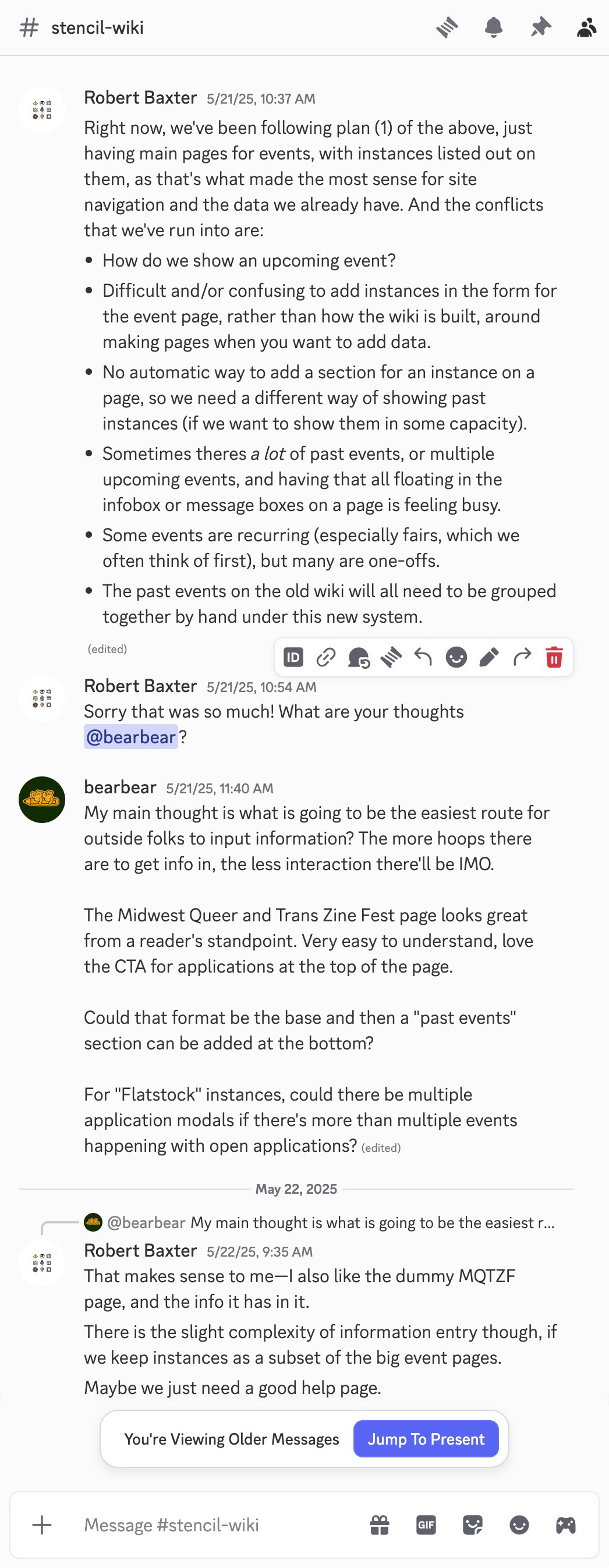

Even figuring these out is a lot of decision making and back and forth in a group discussion: Should there be one page for the Midwest Queer Trans Zine Fest (MQTZF), or different pages for MQTZF 2024 and MQTZF 2025? What makes a "printshop" and a "publisher" different—are they the same thing—can people be both? Should custom ink colors (like Flatallic Gold) be included on the wiki—do we treat them differently from other inks? Thankfully, for these and other questions, we had the wiki best practices guide and a community to talk things over with.

Then, with the objects "defined," we had to actually make them. Each one has a basic template, a form for creating and editing them, an infobox to display data, a category page to list them out, and a bunch of little support modules to display information on them or determine how they can be referenced by other pages. And of course documentation, notes and comments and tooltips and help pages to explain how the things work, how to edit them, guidelines for the info that goes into them, and what work remains to be done!

What's nice is that this whole framework is malleable, and edited using the same tools as the pages themselves. If we decide we want to add more support for equipment, with built out equipment lists and types and resources (so you could find, for example everyone running a shop with a Stitch'n Fold booklet maker)—we can just add that into the spec!

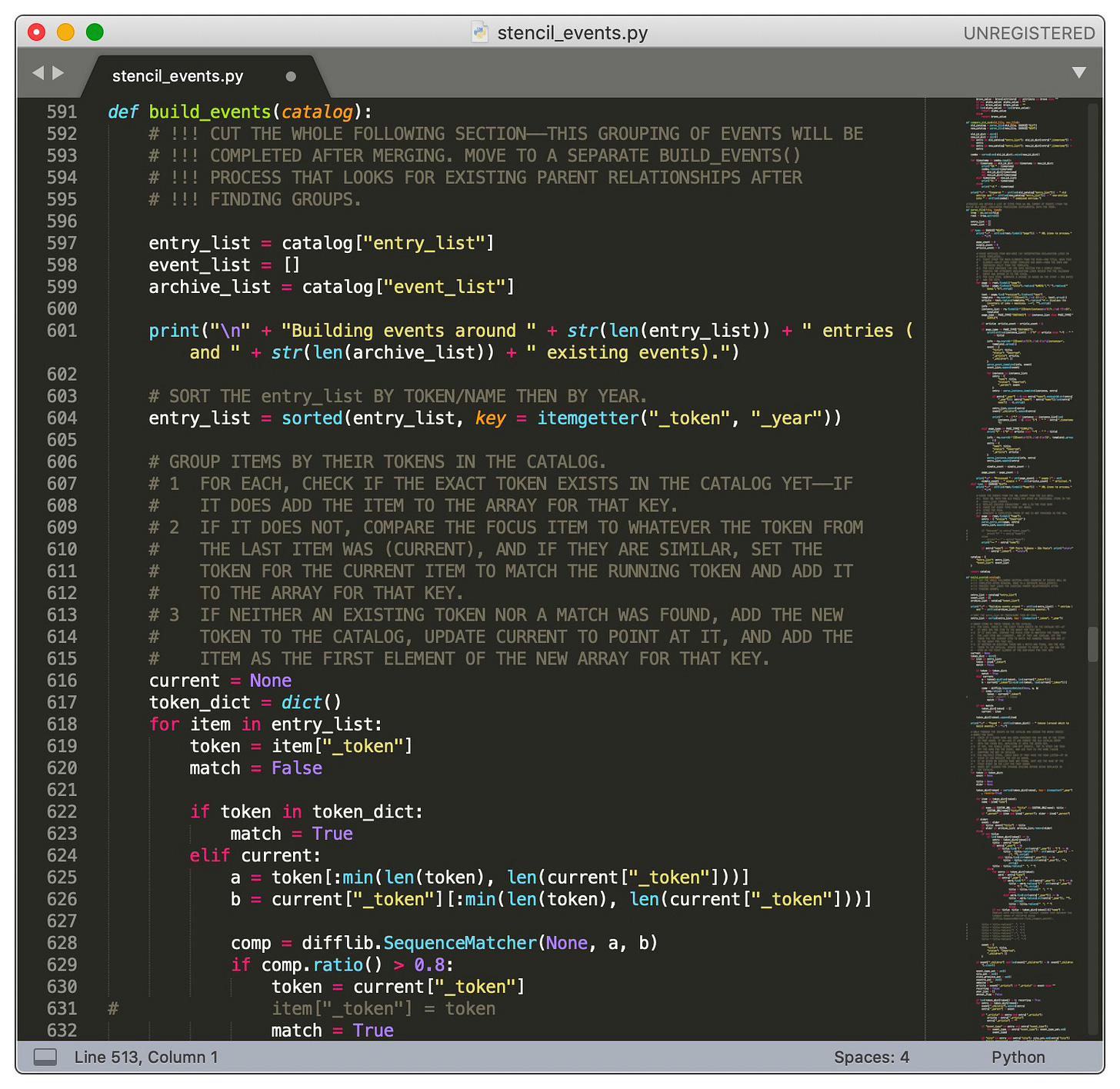

Lastly we had to "migrate" all the content over from the old site to the new site—those thousands of places and hundreds of events. For the most part we tried to automate this—but because the platforms were so different, we had to write a lot of our own tools to help translate information from one to the other.2 And many of the pages we simply moved over by hand (or are still moving over).

Templates All the Way Down

Getting used to wikitext (the source language for wikis) is strange—it's sort of a three-way hybrid (chimera?) of:

A markup language (so you would do something like

''this''to produce italics like this). There’s also some specialized syntax around links, which would use something like[https://en.exploriso.info/exploriso/ Exploriso]to generate an external link like this: Exploriso ↬ or something like[[Events]]to generate an internal link to the Events page on the wiki.Plain HTML (you can use

<b>tags</b>in the same you would use tags anywhere on the web—including complexities of document object model stuff, attributes and styling, custom ids, etc.).A unique syntax of component calls which "transclude" templates (to embed little repeated things in the page, like using

{{cn}}to make the ubiquitous “[citation needed]” superscript appear.)

And this holds true for all parts of editing the wiki! It's for writing the pages, the things the pages are built on, the documentation, etc. This feels like writing and building a website in MS Word 95. And while the markup syntax is mostly simple, and HTML is HTML, that last bit, the templates, take a bit to wrap your mind around.

So here's an overview!

Basic wiki approach is that every “thing” is a page—there’s a single point of reference for every thing the wiki holds, and that is the page for that item. And yet, there are lots of things that will repeat throughout the wiki. In order for those repeating bits to be defined on a page, but show up in many places (on many pages), wikis allow you to embed one page onto another page. They call this “transclusion.”

So you’d define a page that just has something little on it—like the following little RISO logo (we use this on ink pages for official inks).

And then save it to a page called something like “Template:Riso_logo”—then anywhere that we want to invoke the logo we’d just type

{{Riso logo}}and it would appear! The “Template:” prefix hides this little fragment page from the rest of the wiki, so that the whole thing isn’t bogged down in tiny templates (there are 102 templates on the website currently).Templates can also have some variables attached! So the way that we display these colorful little ink buttons throughout the site:

—is with the “ink chip” template. We can plug any ink color name (itself a page name) and it will spit out one of those buttons. The above is created by typing

{{ink chip|Sunflower}}etc. (Actually that little riso logo also is parameterized—it’s a “brand chip” template—so we can also use it to make Ricoh and Gestetner logos, and maybe more in the future.)Templates don’t even need to display anything—some of them just perform invisible tasks, like adding a page to a category, or assigning database variables, or managing redirects, etc.

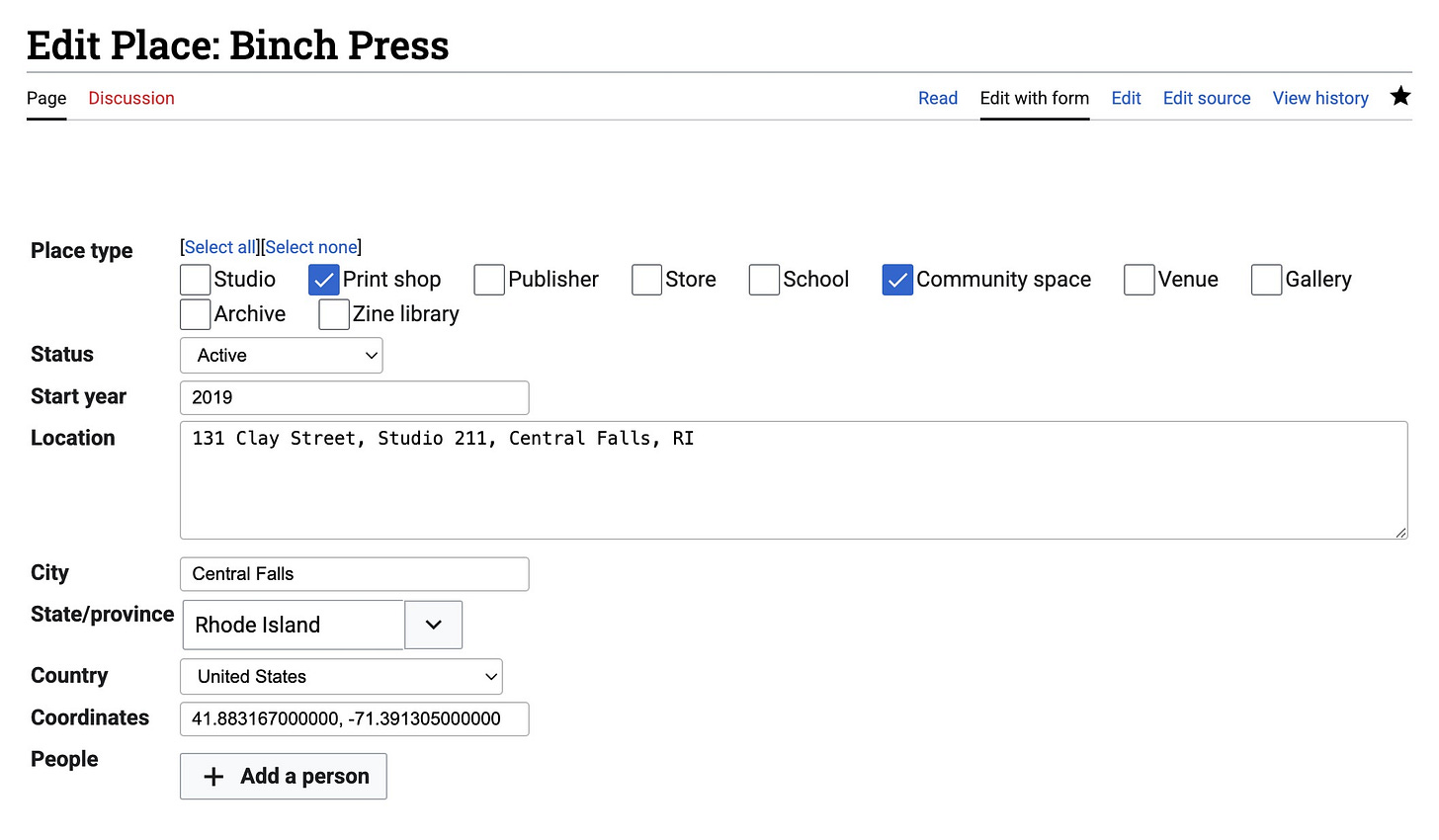

Some templates can have a huge array of variables in them, and do a lot of heavy lifting. Here’s the full code that defines the specs for Binch Press:

{{Place

|status=Active

|start_year=2019

|location=131 Clay Street, Studio 211, Central Falls, RI

|city=Central Falls

|state_province=Rhode Island

|country=United States

|coordinates=41.883167000000, -71.391305000000

|services={{Place/service

|service_type=Print for hire

}}

|website=http://www.binchpress.com

|inks=Purple, Orange, Yellow, Sunflower, Cornflower, Brown, Black, Blue, Bright Red, Fluorescent Pink, Light Teal, Green

|machines=GR3770, GR1700

}}But much of this is behind the scenes—editing of complex templates like this is mostly done through form pages or visual template editors.

If you look under the hood you’ll see that on any given page there might be dozens of templates bouncing around (and each of those might transclude others!)

Speculative Writing & Editing

Okay, that's more or less all of the technical stuff out of the way. Now about the writing itself. I've found it really exciting writing for the wiki!

Part of it is writing with other people—we put all this work into building this space, and now to see people actively using it and contributing, often in ways unexpected—it's a good community feeling. It's a similar feeling I get when facilitating shared equipment in printshops: setting resources up and systems for how to use them, and then seeing that people have used them to make projects I had no idea they were thinking about—or to see strangers come to the shop and make something beautiful. And it happened so quickly! Within a few days of launching it and opening it to editors (after months of building it in the odd hours) it had a bunch of new edits and pages and people going through and slowly adding their knowledge.

There's also a loss of the burden of authorship, when you are passing a voice around amongst other authors. Everything is editing, and everything is edited! You don't own the thing you wrote, you share the thing we wrote. And that's quite nice. We have our own stylistic squabbles, like whether risograph should be lowercase, reflecting an object which (for us at least) is common—or Risograph, the name of a branded product. Though we try to resolve them with things like a styleguide (though this too is edited by the group). This shared authorship also eliminates the need for something to perfect, or even complete—you can come back to it later, or someone else can. It's a reassuring collective, sort of mutely fumbling around in each others work, sometimes leaving notes of what we've changed and why. I've seen evidence of adversarial editing, on larger wikis, but it doesn't seem to be in the spirit of the thing! I'd be curious if there are any projects that use the wiki structure for creative writing.3

The other part is that writing for a wiki, especially one in the early stages of its existence, feels quite speculative! See, a wiki generally covers a lot of content—they can be huge, and are constantly building upon themselves, but it's not the sort of thing that lives behind a curtain and then one day is revealed in full. It starts small and then gets built up bit by bit in public.

The means for this is a weird manipulation of the fundamental building block of the internet—the hyperlink. At its core the internet is nodal—it's a set of entities (websites) and connections between them (links). Now a lot of additional stuff has been built upon this—hierarchies and search engines and databases and endless algorithmic feeds and all that other nonsense. But a wiki is almost quintessentially that core—it's just pages and links! Working in a wiki feels like looking at a protozoan creature as a more complex creature yourself, it's like looking into the past in the context of the future—it feels old, prehistoric, but that kind of resonant, archetypal ancient. But it has places to go that are their own kind of endless.

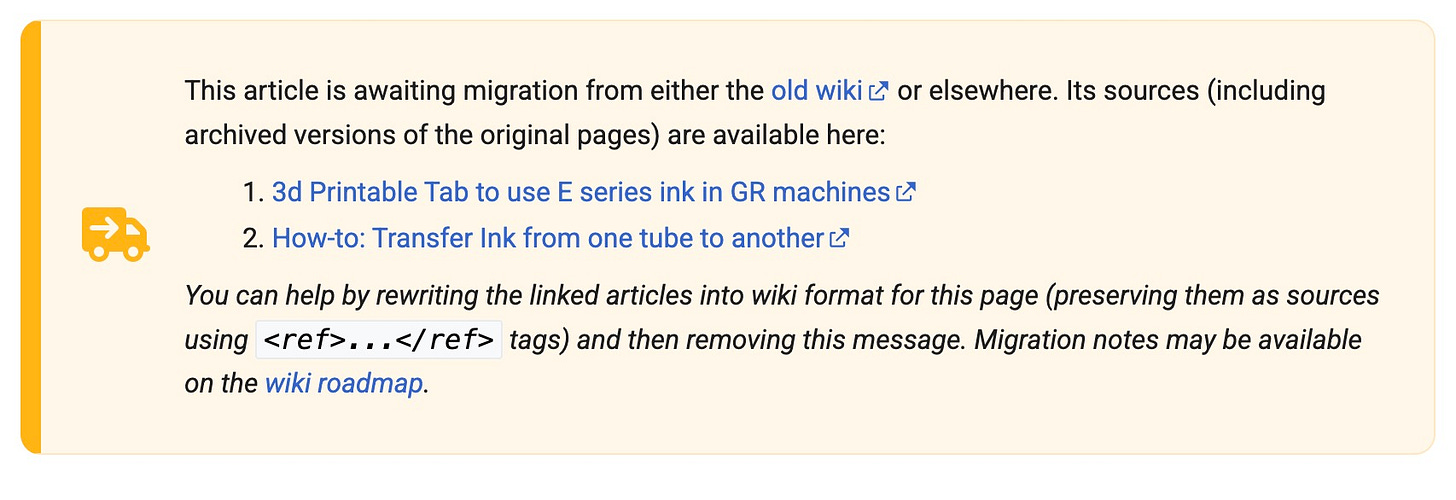

While most of the web treats a link that doesn't go anywhere as broken, on a wiki it's a marker of a place where some human person, some other editor, thought that this thing could grow from here. These are "red links"—they're some bit of text that are supposed to go somewhere, but they don't yet—they point to a page that hasn't been written. A whole body of information could be gestured towards by a wiki with a single article whose red links point in the direction of what it could one day be. It's all very Borges—references and notes and citations that invoke a large and complex and slightly different world, from the bounds of a short fragment of story.

And it's nice! As a writer, you can be musing along, illustrating some point or writing out some sort of process, and mention something and think to yourself "this doesn't exist yet, but it should" and make a little link to something missing. And as a reader you can see one of these signposts leading into the mist and decide you have something to say here—some new writing to put on the wall.4

It's strangely hopeful.

Current Happenings

I’m in Los Angeles today! Sitting in frog-town by the LA river—waiting for some repair visit details to be scheduled. I popped into town to table at RAZ, and then join the conversation at a lovely riso hangout that Natalie Andrewson put together. While here I’ve visited Punch Kiss Press, and I’m due to say hello to Heavy Manners too! Then tomorrow it’ll be a train ride up to San Luis Obispo to visit Jayme Yen, and then onwards to SF, where I’m set to see National Monument Press, Awkward Ladies Club, Floss Editions, Christina Hu, and Tiny Splendor!

Next up on my docket is to write a bunch of the technical articles and resources on the wiki! I’ve walked so many people through common repairs on reddit and discord and through texts and phone calls, so it feels good to be gradually building out some more stable resources I can send people to. Here’s the ones I’ve written up so far:

Drum color codes—about reprogramming drums.

Screen printing with riso stencils—a useful hack, expanded from an older article by Topo Copy.

Moving a two-drum risograph—there’s some important securing-of-stuff to do beforehand so that the machine is safe to travel.

Fix thermal-pressure motor lock—the classic TPH gear replacement procedure (original article by RISOFORT—I’m slowly generalizing it for all Z+ machines).

I recently moved to Minneapolis! I’ll finally make my way back there after quick stops in Chicago (for Pretty Good Fest) and Detroit (for Detroit Art Book Fair). Not sure how to write about this one yet, still exhausted by the process and still within it, but so thankful to Late Night Copies and Taxonomy Press for inviting me to the midwest and making this move even possible.

Platforms come with different degrees of expandability. Some are fairly prescribed, like a spirograph set—you can make lots of different things right out the gate but all within the same sort of shape (stuff like Google Docs, or the old Live Journal, Substack). Others are much lower level, like a drafting table and tools—you still have some limits (it's going to be pencil or pen on paper) but you can do a lot more with it, though it's more difficult (these are like Wordpress, or node.js, or things like that).

This was my first time using Python—horrible language. Very beautiful, very powerful, and theres a certain character to it that's fun—but with a syntax that casts aside all other conventions from other scripting languages. I don't consider myself a coder, I hate doing it—and every time I need to I have to relearn everything and then forget it all again. I do not look forward to having to relearn Python. At least it is well documented.

Upon a reread, I do know of one—The SCP Foundation, which documents a strange and subtle folk horror, interwoven with our day to day reality.

My father told me before about a game he used to play on the Stanford campus, in the early days of computers and networks, called CAVE (actually it's Public Caves, from 1973—it took a while but I found it). This was a text-based game, of the form:

YOU ARE STANDING AT THE END OF A ROAD BEFORE A SMALL BRICK BUILDING. AROUND YOU IS A FOREST. A SMALL STREAM FLOWS OUT OF THE BUILDING AND DOWN A GULLY.

—but rather than being preset dungeon for you to explore on your own, a la William Crowther's Adventure (1976) (from which that line is taken—one of my favorite pieces on the game is "Somewhere Nearby is Colossal Cave"), you are exploring a world created by the other players of the game. In the game of my father's memory, you would explore a world of rooms, with passageways leading to other rooms. Each room had a name, and some writing on the wall that you could read. If you were the first to visit a room, you got to name it and write on the wall. It wasn't some realtime interaction, but it was a slowly evolving, collaboratively edited story, with new rooms being added in each play through.

In the other retellings of the game that I can find (and its inclusion in the People’s Computer Company), it was actually even more similar to a wiki—you had the ability to add writing ("graffiti") to the walls of any room you visited. And you could build a room leading off of any other room, or add connections between existing rooms. Pages and links, again. A platform in its own right.

Congratulations, amazing work!