Risography in Small Publishing (Interview)

Q1. "Could you tell me about yourself and your background in detail?"

This post is a little oddity—in that it’s more self reflective than I usually get in my writing. I was interviewed about my work recently, and really liked the questions that were asked, and came up in follow-up conversations—so I’m sharing out a portion of that interview below! Normally I try to keep my voice and focus on the rest of the print world (I’m reticent on the internet for many reasons), but I think this small exposure will be survivable.

First though some timely travel news:

Over the next 4–5 weeks I’ll be visiting NYC, Portland (ME), Providence, and Miami (in roughly that order). I might also be visiting Mexico City for Index Art Book Fair (if I can find a place to stay).

I don’t have exact dates yet, but I’m headed to New York this evening, and will probably start making my way north right around the new year, then headed to Miami around January 11.

If you’re in those cities, and would like a repair visit (or just to hangout and talk shop), please send me a message! The docket is starting to fill up but I still have some downtime in all those spots.

As always, my full public travel schedule is available here: Travel Plan [Public]

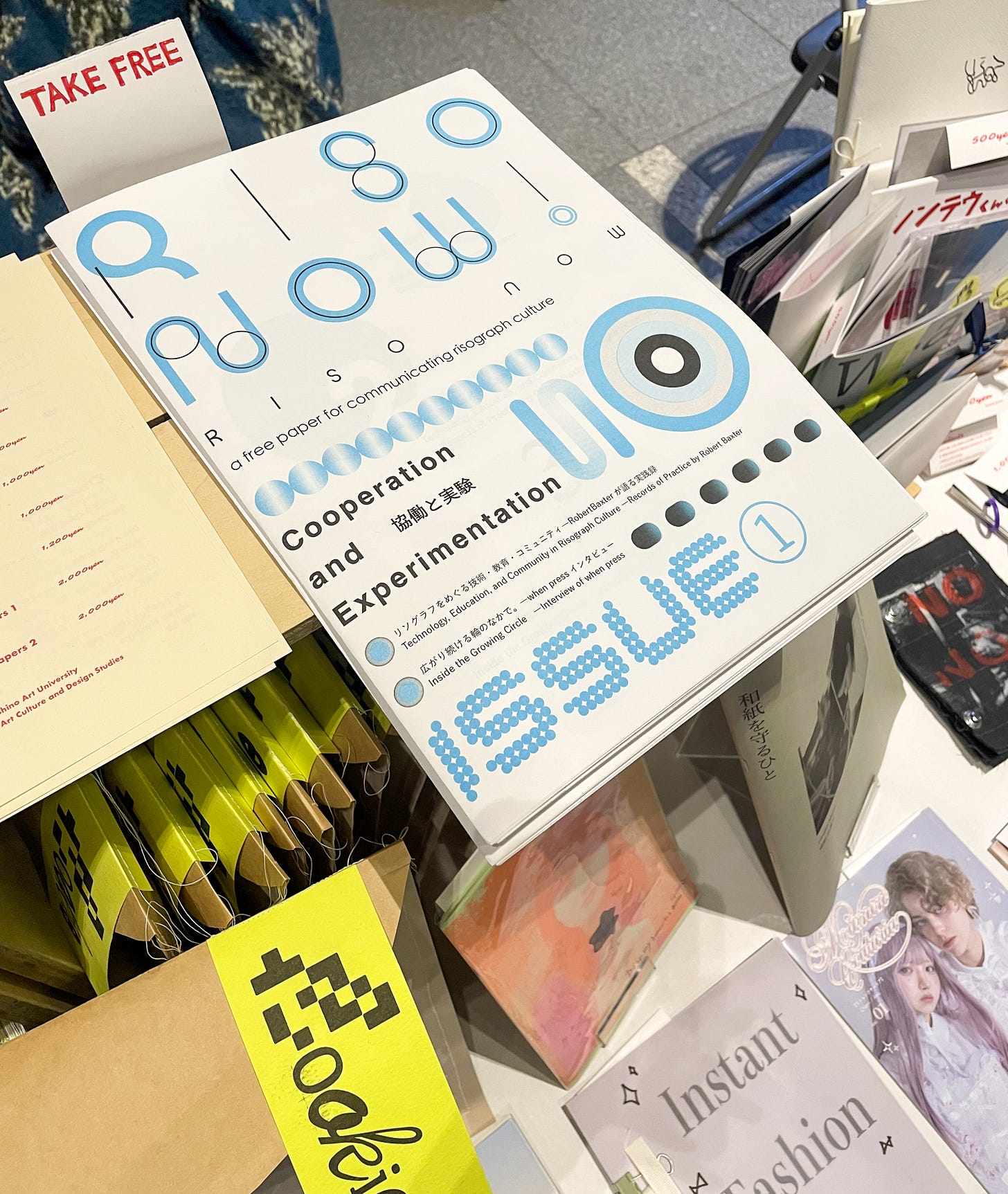

A few months ago, Haruka Amano reached out to me about a risograph journal she was developing in Tokyo, and asked to interview1 me about my work as a technician and some of my writing about community print culture.

“I am currently working on my graduation project, producing a free paper dedicated to Risograph printing. As someone who has created zines and magazines using Risograph during my studies, I have developed a deep passion for this medium. My project explores Risograph culture, covering the people and communities surrounding it, aiming to create a form of media that sits between a specialist magazine and a cultural journal.

“… For the first issue of my paper, I am exploring the theme of ‘the unknown’—focusing on how people explore Risograph printing from a place of uncertainty …”

I really appreciated how thoughtful a lot of her questions were, and she’s given me permission to reprint them here—so here’s an abridged version of that interview!

Q1. Could you tell me about yourself and your background in detail?

My education took a complicated route—I entered school interested in both art and engineering, then spent a year in a mechanical engineering program (while taking mostly art classes). I was frustrated with how theory-based the program was, I wanted to get my hands dirty and work with gears and motors and systems.

I dropped out for a few years, and eventually returned to school in a design program, as a compromise between art and engineering. Outside of school I worked a few years in a small design firm as a strategist, while developing a small zine practice on the side. The design industry in the US (and many other places) is essentially a marketing + advertising factory, and I was very quickly disillusioned, so I saved up for a few months worth of expenses, quit my job, and started trying to work in community art spaces!

Q5. What initially drew you to the world of risograph printing and independent publishing, especially zines?

The easiest answer is that the community around small press is filled to the brim with the most generous, kind-hearted, dedicated, and genuine artists I know. Even though we are all constantly scrambling to make ends meet, we aren’t doing it in isolation. Everyone here is a teacher, everyone shares resources, and everyone is in this field because they care about print media and the people who print it.

At every step of the process I’ve had people to learn from, commiserate with, and who would lend a hand without asking anything in return. I think this is beautiful! And rare, in our world of manufactured scarcity and competition.

I think much of this is in the nature of our work:

We operate at a small scale, making small projects in small runs. There’s some humility that comes from this, none of us are heroes or celebrities—but we’re all artists. We each touch each item we make, we’re directly connected to the product that comes from our craft. And all of us have ink-stained hands to prove it.

Our costs and profits are low enough that we fly under the radar of a lot of the capitalist machine. In other words: you might be able to survive as an artist in small press, but you won’t get rich from it, so it doesn’t really drive or depend on systems of infinite growth—we’re much more concerned with finding a balance and getting the materials we make into the world!

We interface with the public (a necessary part of publishing), so its very on the ground and social, but with other small press people, and readers and artists outside of this world.

We use equipment and workflows that often cannot function without other people. We can’t do it alone, so we do it together, and it is better for it!

Q2. You seem to have many roles — educator, researcher, technician, repairer, and more. Could you explain what each of these roles involves in your work?

I sort of think of all of these roles as the same thing! Being an educator is just the pro-sharing version of being a researcher. So, I am driven to learn things, and when I learn things, I want to distribute that information, which for me looks like both teaching (often in workshops and just as an approach to explaining what I’m doing and why) and publishing (which is mostly a writing practice, with an occasional print project of my own emerging from those writings).

I also like providing a service to my community (it’s part of that teaching impulse) and it turns out that what the small press community needs is a technician. Once I learned how to repair my own machine, it was something that immediately all the printers and artists around me needed help with too. So it became one of the things I know a lot about, and now I am teaching and publishing a lot of repair resources specifically.

Q4. I read on your Substack that you once ran a small print shop.

What kind of place was it, and are you still running it now?

It was a small print space in the back of a larger painting and sculpture studio. I had joined as a member artist at the beginning of 2020, and found an old risograph (FR3950-ɑ) and drums for sale, and moved them into the space. In the 3–4 years I was there, my principle practice was figuring out how to make the printshop an accessible resource for other artists! This involved:

Learning to repair the riso (which was very broken) and drums. Fixing this first machine slowly, over the course of a few months was a struggle! It was hard to find resources online and in the community, and I had to learn a lot about mechanical systems using only the damaged machine in front of me. But it’s how I got into repair, and why I’m working to build out resources that are available to other operators!

Teaching other people how to use it! (And myself in the beginning.) The space was pretty informal, so we never offered the classic riso intro workshops, but we did a lot of 1:1 and 1:2 mentorship, and taught resident artists and students how to print on our equipment. And we wrote lots of little guides, pieced together from the user manuals and our own drawings and photographs.

Creating programming that used the risos—the largest of which was project support. Before each major small press fair we’d invite our arts community to print a project with us. This resulted in roughly 20–30 new publications each year from different artists (for many, it was their first publication). Each of these artists either ran the machines themselves or played shop assistant during the production. And in the week before each fair we’d hold binding + assembly parties where everyone and their friends would come learn how to collate, or saddle stitch, or staple, or use the guillotine, and we’d all make each other’s books!

In addition to this fair printing, we’d also use the risos to create materials for most of the exhibitions and performances in the space (some of which were built around this printing practice).

Developing systems for shop operations: figuring out what materials cost, how to run inventory, what kind of education was necessary to safely use the risos, how to pay teaching artists, and how to sell zines at fairs and all that. As well as building systems around those systems, to determine how these patterns could change and grow (or shrink) with the shop and the artists there.

As more and more artists became involved, a lot of this work was dialogue based. Meeting, discussing, learning how other shops ran, comparing budgets, and figuring out how we could all have the agency to run our practices together in shared space.

The printshop was rapidly collectivizing and struggling for its own autonomy, but this caused a lot of conflict with the way the larger studio space was run. Sharing space is difficult! And requires a lot of good faith communication, conflict navigation, and collaborative values. Ultimately the printshop we were building didn’t align with the way the studio functioned—when I left that space I committed to making myself a resource more broadly to the wider print community.

Q7 + Q13. Besides machine repair, do you also get requests for advice on studio management or operations? If so, could you share some examples? Could you share your thoughts on what you believe is the most effective or ideal system for running a print shop that uses risograph?

I get lots of questions about studio operations—in part because I try to emphasize that these policies are actually a really big part of keeping equipment running!

In all the community places I’ve visited, I’ve noticed that the health of the risos is really dependent on the health of the studio and the systems they have in place there (plus, as described previously, I’m very much a systems person). So when I started running repair workshops, I made sure to talk about how the risos are used, as a form of preventative maintenance. And these methods of use are now things I look for, gather, and share—from all the places I visit!

So now, if I’m spending a day or two working on the machines in a community space, I try to also have a consultation meeting with all the main press operators to figure out a system that works for the studio. However, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to shop management. It really depends on who uses the machines, and what kind of space they’re in, and what the goals of the community are!

That being said, there are common patterns—here’s some of the big ticket items:

Managing access to the equipment is a balancing act! On the one hand, you don’t want to gatekeep the gear, on the other, if it isn’t used by people who know what they are doing it can be harmful (to both the equipment and the people). So generally there’s some kind of training required to use the machines, and how much training is needed depends on how the machines are used and managed.

I think of it like this: there’s a series of things needed to be done to run the risos and keep them running—that’s just a list of tasks. If you take that list, you can split up the components of it into different responsibilities that different people can hold—then so long as people are only doing tasks they know how to do, they can run the riso safely and with confidence, and there’s always someone who can do all the various things the machine needs.

This is (roughly) the list:

12345678901234567890123456789012345 I Turn the riso on and set it up for printing II Load paper III Change the drum(s) IV Scan an original (and select scanning settings) V Send a file from a computer (and select driver settings) VI Position the printed image on the page (registration) VII Adjust paper feed settings VIII Turn the riso off and close it up IX Load a stencil roll X Load an ink tube XI Monitor issues in printing XII Document issues in printing XIII Clear paper jams XIV Clear stencil jams XV Clean the feed tires XVI Clean the machine XVII Clean the drums XVIII Replace common parts XIX Replace uncommon parts XX Calibrate the machine XXI Repair the machine and drums XXII Teach people how to print XXIII Manage inventory of consumables XXIV Manage inventory of parts XXV Communicate shop status XXVI Maintain systems in the shop XXVII Build systems for the shopEveryone who uses the printshop doesn’t need to know all these things! Maybe the regular printers just know I–VIII (they’re in a rough order from simple to complex, but it’s not exact), and then a shop monitor knows the next few items, and the last are managed by a local technician. But these are all things that all machines will eventually need (and it’s a very simplified list)—so it’s good to plan who is doing what!

Having a plan for what to do when something goes wrong—AKA a maintenance plan. What happens when a machine throws an error code, or makes a loud noise, or shuts itself off? What happens when someone drops a drum? Or when someone feeds a sheet of transparency and everything gets inky? What happens when the paper can’t feed anymore?

Printshops need some system of reporting what has happened, addressing it, and then having a backup plan. I personally like having an open discussion platform of some kind, so when something goes wrong with a printer, the artist using it can shout out to the rest of the group: this has happened, what do I do? Having a single-point-of-contact is also useful—this is the classic style, call this number for technical support. I am that point of contact for some studios—but much better if it is someone who also prints on those machines!

As far as a backup plan goes—things go wrong all the time! How will you finish a project when something has gone wrong? I think redundancy is deeply important to build as soon as you are able—a second machine, additional drums, even partner printshops that you can print out of or send work to when you need to. We all need this sort of support sometimes!

The last one is much more difficult, it’s the culture of the space. I tell people a lot that they should be kind to the riso and be kind to yourself. The culture of a printshop is a big part of being kind to yourself—it’s sort of how you can be kind to the community and the community can be kind to you. But this is a hard thing to put your finger on—it comes down to: Do people feel happy in the printshop? Do they feel that the equipment is cared for, and that they are cared for? Do they feel that they matter in the community? That they are heard? Do they feel they are supported? Do they feel they are able to make mistakes, or fail? Do they feel they are able to grow?

Part of traveling to other spaces is seeing how other people do it, what feels healthy, and how I can learn from their mistakes and they can learn from mine.

Q14. As you’ve said before, there’s no universal system that works for every print shop. Even when it comes to risograph workshops or access models, each studio has its own unique character, which is fascinating. Do you think these different access systems also shape the way each studio’s community forms and functions?

This is an excellent question—I believe the answer is: yes, the means of access necessarily governs at least some patterns in how community develops around it. Because access affects a lot of things—not least of which is the relationship between the different artists in the space, and the relationship between each artist and the space itself. And that forms the foundation of any community, those relationships. I suppose it’s like the way a crystal or lattice forms around some small nucleation point. The shape of it is scaled upwards, and if you look at the outside shape, you can discern what the core might hold. I don’t know that access is the only thing within this core, but it’s certainly one of the components at the root of community.

(Some loose thoughts follow.)

Are you a student of the space or the people there? Perhaps your relationship with a printshop is through a required course—where do you go after being a student? Are you learning while you print—do you require a teacher? Are you a teacher yourself? This sort of pedagogical hierarchy is an established model in printspaces, with master printers, journeymen, printers devils (apprentices), etc. But it is not the only model—what other ways are there to build knowledge than the teacher/student relationship?

What does this cost you—do you pay by time, by material, not at all? Is this an investment? An economic necessity? An economic burden? Do you scale your projects to fit within the constraints of a ream of paper? Or within a 2 hour rental window? What income do you make from your work here—from the labor, the sales of your work, or something else? Who can afford to access the printshop?

The printing, ostensibly, is what a printshop offers—but community printshops are often also a bindery and studio, sometimes a storefront too. Even the small hand tools that a printshop might hold can be difficult to find or access elsewhere—things like staplers or a good hole puncher—not to mention specialty tools like punches and awls and shears and even the right kind of glue or thread or paper. So what is accomplished in this space, and what is accomplished outside of it. Is it a place you can linger? Or read? Is it a place you can develop a work, or is it simply a place where work is produced?

Do you work together in the shop, or independently? Are you sharing space simultaneously, or bracketed through the day? Do you share tasks, or do people have their own roles? Are you working on your projects, or the projects of other people too?

What about contributing your own skills? Is this a place where you have something to offer to the other people there? Is it a place where that has material value? (Perhaps you are exchanging your services for access.) Are there policies asking you to share, or expecting, or requiring you to? What kinds of skills are valued?

What ability do you have to affect the structures and systems which govern how you use the space? Can you make changes there—improvements, for yourself or others? Is there a means of acknowledging things which do not work? I am a major advocate for the importance of agency as an artist—especially in the world of small press! Knowing how to publish, and having the means to do so gives you some agency over the small media world around you and in your community; it is empowering. I think publishing is an agency building activity. The agency to make things of your choosing. But even more powerful is also having some agency over the environment in which you make things. It’s more difficult though, because it’s not only you with agency, at that point, it’s everyone around you too, and you all must navigate how you make decisions, and how you take actions together.

Whatever happens in the shop is also only part of an ecosystem—what are the other needs of the community and where/how are they met? This is why you can’t really look at studio structure and policies in isolation—they require the context of the place and way in which the studio is situated—and the context of the people within it. The question of “what kind of community does the printshop operate within?” is just as important as the question of “what kind of community does the printshop create?”

I don’t have a methodical body of research around this, but it’s a question I’d also like to ask of others and interrogate a little more deeply.

I also don’t know that there’s a “right” answer to any of those questions, or even a right way to get to an answer! That individuality of print spaces and their histories is also why I like this work, and this line of study.

Q11. On your Substack, I was struck by how openly you discuss topics such as profits at book fairs or how you pay your helpers. What motivates you to share this kind of information so transparently?

I have to reference a few different projects for how and why I do that—but the simple answer is that small press is beautiful in part because it is accessible. In scale of projects, the process of printing and assembling them, and in what it costs to make them—but while the first two are really well documented, the third one, the money side of things, is very opaque.

Since I already document all of this for my own budgeting (I have very low margins) I try to share it out, so that other people, interested in making similar work, know what to expect.

The actual practice itself is based on is the following:

The Detroit Printing Co-op was a community print space in the 1970s (it’s beautifully documented in a book by Danielle Aubert of the same name)—in the colophon of the books they made, they listed everyone who was involved in the production process. This included a blurb which said something akin to: this book was not easy to make, but we made it, and you can make one too.

When the Whole Earth Catalog published their final issue (at least as a part of that endeavor), The Last Whole Earth Catalog, it included a series of pages at the back of the book,2 just before the index, which outlined their entire process. Budgets, tools, personnel, what the challenges were, recommendations, etc. Again, their goal was to allow others to follow in their footsteps.

Be Oakley’s press Genderfail, publishes a lot of material about how they operate—full budgets for the operation, what decisions they make when taking on projects, and how things developed over time. In particular, their book Publishing Now: GenderFail’s Working Class Guide to Making a Living off Small Publishing also goes into detail about how their share these numbers with their contributors for each project, the production cost, sales at fairs, how much everyone has been paid, etc.

Many other press friends practice financial transparency in their projects or have talked about their logistics! Including Late Night Copies (Own the Means of Production & Share It + End Application Fees), Anemone (Notes on Artist Publishing), and bearbear (heybearbear.substack.com).

What things cost, how to plan for them, how to pay people and myself—these were all questions that I asked a lot, early on (and still ask), but didn’t have answers to. So I share all this also so that someone else starting out might have a little bit more to go off of than I did.

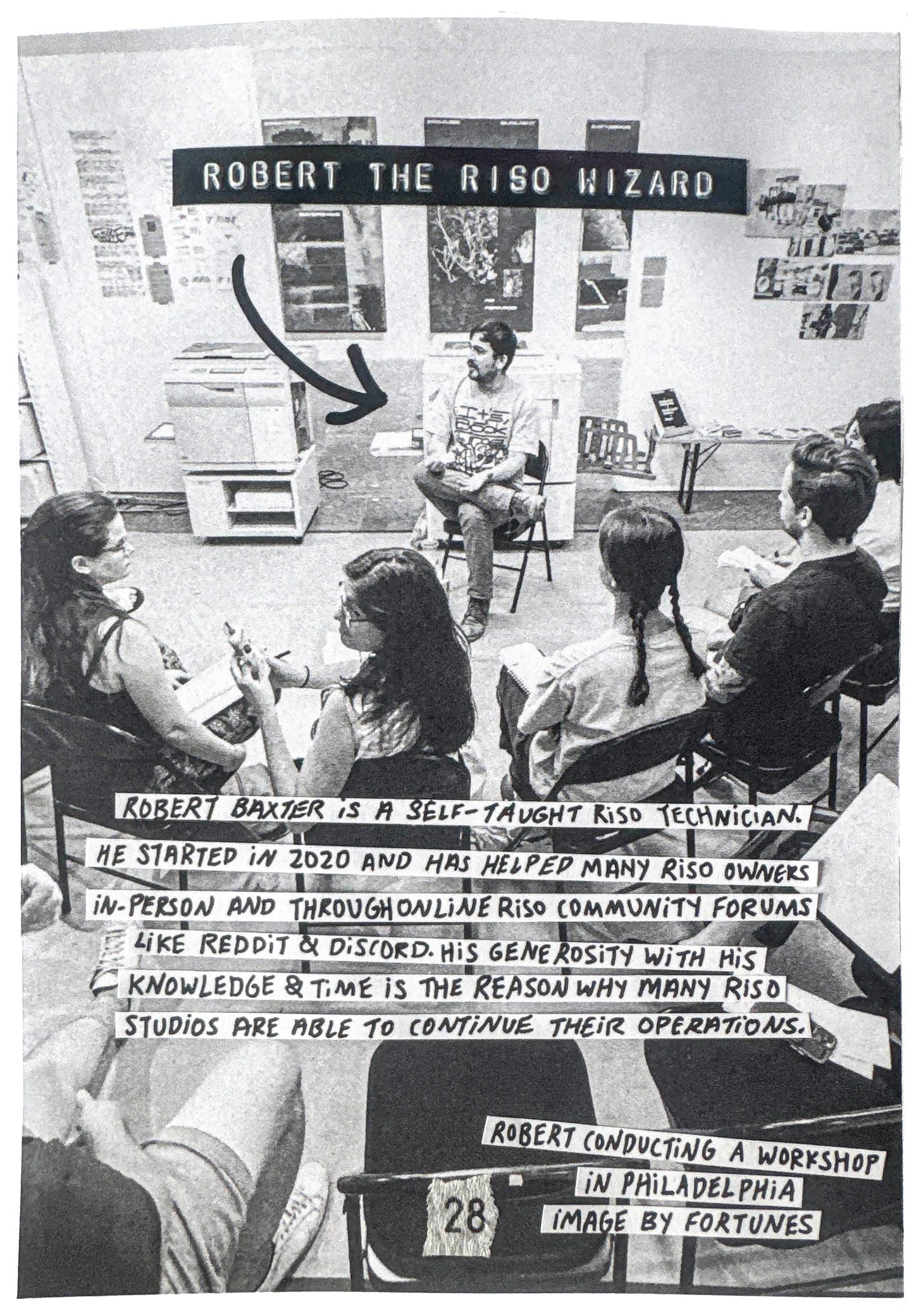

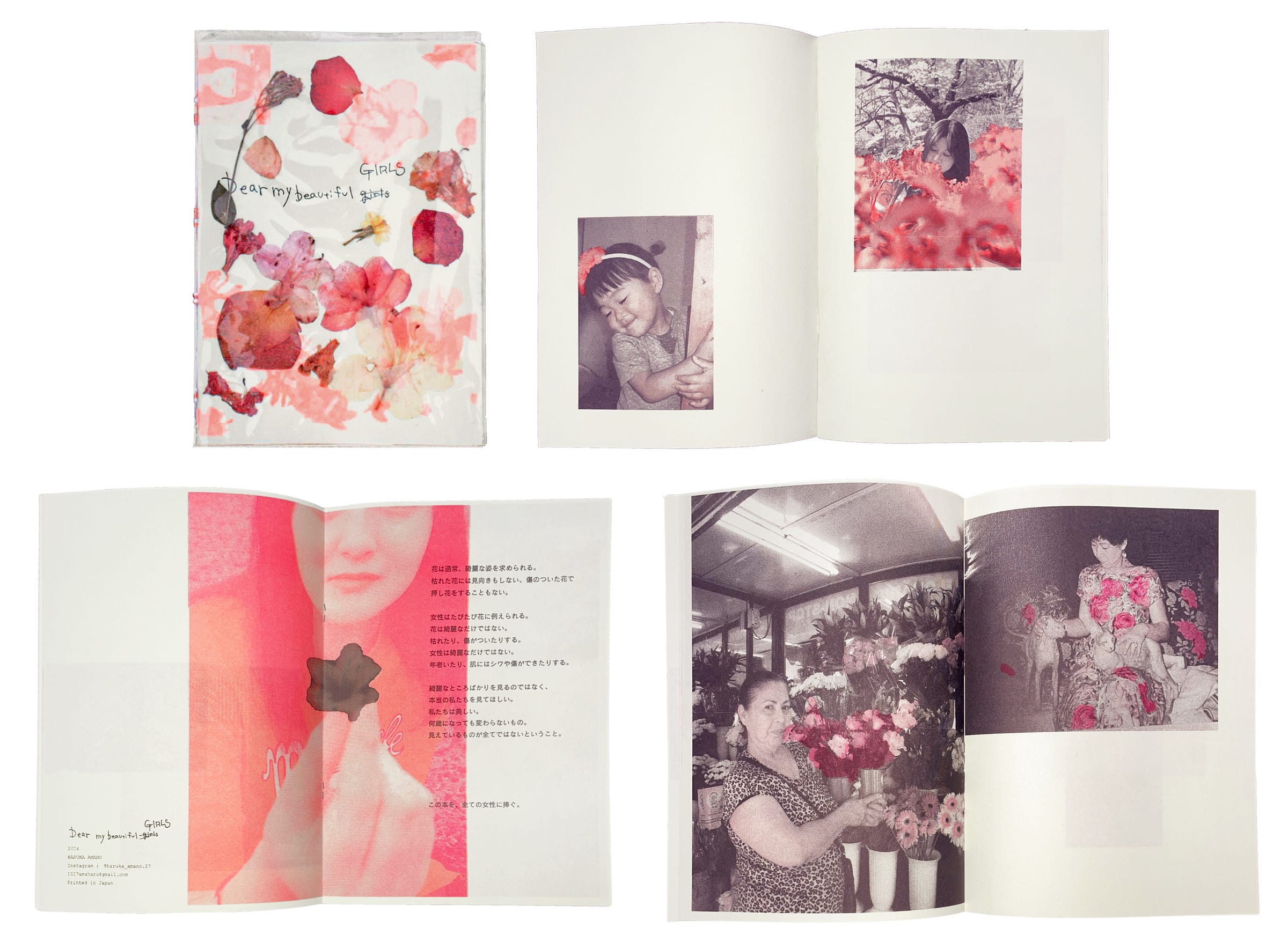

That’s it for the interview! Thanks for reading! A print version in Japanese and English is currently available at the Tokyo Art Book Fair. I’m including images of it and some of Amano’s other work below.

Current Happenings

Reminder—shoot me a message if you are in NYC, Portland (ME), Providence, or Miami (also maybe Mexico City) and want a visit!

This substack has been going a bit more slowly, as I am putting a lot of writing effort (technical writing anyway) into stencil.wiki, to build out some of the resources on there. Here’s what’s new and in-progress:

There’s now a pretty robust help page on how to contribute to the wiki! It gives step by step instructions on getting started, information on how wikis work and how to edit them, and our current task list for editing it and getting it up to snuff.

Amelia Greenhall (of Anemone) and I have been working on building out the print position articles—going over best practices and calibration. I still need to build out the GR/FR calibration process, but the RP/RN and Z+ articles are good to go (though may need some more images).

I recently added some maps and listings tracking the usage of different ink colors! So if you want to see which studios are using which colors, you can just scroll to the bottom of any ink page (I was using Yellow to test, so that has some nice article content too). With the way we’re managing data on the wiki, it’s now really easy to collate information about usage—for example, the most commonly used inks are: (1) Black, (2) Fluo. Pink, (3) Yellow, (4) Blue, (5) Green, (6) Bright Red, (7) Fluo. Orange, (8/9) Orange + Medium Blue, (10) Red, (11) Sunflower, (12) Aqua. I’m also planning on running some analysis on what sort of CMYK process setups are used in different places.

Pretty soon the machine pages will also be extended in this way—so you can see who is using each model (of both duplicators and bindery equipment). For now though, the update is that there are maps on the series pages (for example, you can check out everyone who is using the RZ series.

More exciting for machines though, is that all the tutorials we’ve been writing are now tagged for the machines they are applicable to—so if you go to the GR series page, it lists out all the relevant tutorials for GRs. This includes a huge tutorial about the most common repair I do on these machines: retiming the main drive (GR/FR).

I’m still unpacking! Always more books in boxes.3 But I really love what I have been able to experience of Minneapolis so far. It seems like a really nice city to come home to, and to figure out this next chapter of my/our practice.

There are a couple other interviews that I gave a few years ago, but that was before I really had a writing practice in this way—although maybe I’ll find them and ask their artists if I can reprint those too!

This section is called “How To Do a Whole Earth Catalog”—very straightforward. I reference it often, both for the logistics of production in this time, and as inspiration for transparency and documentation.

A clear reference to the quintessential children’s classic pop-up book More Bugs in Boxes.